Disability advocacy organisations around Australia are currently busy:

- providing individual advocacy support to people with disability during the Disability Royal Commission processes

- representing systemic issues through making submissions, or

- providing information and promoting awareness among community members about contributing their experiences.

Advocacy at public hearings

The experiences and insights of advocacy organisations and their personnel have featured prominently in a number of Disability Royal Commission public hearings:

- Hearing 2 – Inclusive education in Queensland

- Hearing 3 – The experience of living in a group home for people with disability

- Hearing 4 – Health care and services for people with cognitive disability

- Hearing 5 – Experiences of people with disability during the ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic

- Hearing 6 – Psychotropic medication, behaviour support and behaviours of concern

- Hearing 7 – Barriers to accessing a safe, quality and inclusive school education and life course impacts

- Hearing 8 – The experiences of First Nations people with disability and their families in contact with child protection systems

- Hearing 9 – Pathways and barriers to open employment for people with disability

- Hearing 10 – Education and training of health professionals in relation to people with cognitive disability

- Hearing 11 – The experiences of people with cognitive disability in the criminal justice system

- Hearing 12 – The experiences of people with disability, in the context of the Australian Government’s approach to the COVID 19 vaccine rollout

- Hearing 16 – First Nations children with disability in out-of-home-care

- Hearing 17 – The experience of women and girls with disability with a particular focus on family, domestic and sexual violence (Part 1)

- Hearing 18 – The human rights of people with disability and making the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities a reality in Australian law, policies and practices

- Hearing 19 – Measures taken by employers and regulators to respond to the systemic barriers to open employment for people with disability

Click on the video links below to hear disability advocates and self advocates speak at these hearings.

Measures taken by employers and regulators to respond to the systemic barriers to open employment for people with disability

22 November

AED Legal Centre Principal Legal Practitioner Kairsty Wilson

Kairsty Wilson

“…I think particularly during the period of employment, the majority of people with disabilities wouldn’t know of their rights. There is obviously concern, for example, disclosing what their disability is, how will they be treated, will they be treated differently if they disclose… So at termination, though, I think that there is perhaps a little bit more awareness, because it is occasionally on the news and that sort of thing, about people being terminated from employment and that. So, yes, I think at that time they might be aware that they do have rights. They often don’t know about the time restraints though – you have 21 days to put in your application. …we do get cases where they are out of time and then we have to decide, is it worth the fight…”

The human rights of people with disability and making the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities a reality in Australian law, policies and practices

8 November

Our Voice SA Chairperson Ian Cummins and Self Advocate Rachel High

Ian Cummins

“Human rights, to me, I spent time in an institution when I was 19 years old, I never had any rights. When you live in institutions, that — you got rules you have to follow. When I moved out, I learned the hard way. I pay me own bills, I’ve got people for meal breaks, I don’t tell what time you have to be in, what time you have to have a shower, what time you have to be home and all that. Part of equal rights is part of that, do what you want to do out of the community.” “ We got the same rights like anybody else that hasn’t got a disability at all. People don’t know they have equal rights until somebody tells them.” “I want to see more people with disability have more of a say. You know why? Everybody makes decisions for you and half the time it’s not the right way. But at the moment, not enough — they don’t ask people with disability, they don’t go to the real source, people with disabilities, at all. They always ask people what works with people with disabilities and all that, but I would like to, yeah, see more people with disability be able to have a lot more.”

Rachel High

“…the right to be independent, like in your own home and in your own communities, I see that as a human right. The right to explore, you know, the right to be who you are, not what you are… some people can learn about their own rights and how they — how they actually get that, you know, from other people, so like around them, like people that you’re a neighbour with or someone like that…Sometimes you know, we’re not going to a library or a museum or something, and so it’s our …right to explore, our right to learn, you know, that’s how you get [human rights].” “…doing the workshops, to learn about their human rights, where they have the right to go, where they have the right to be; that’s how you learn…”

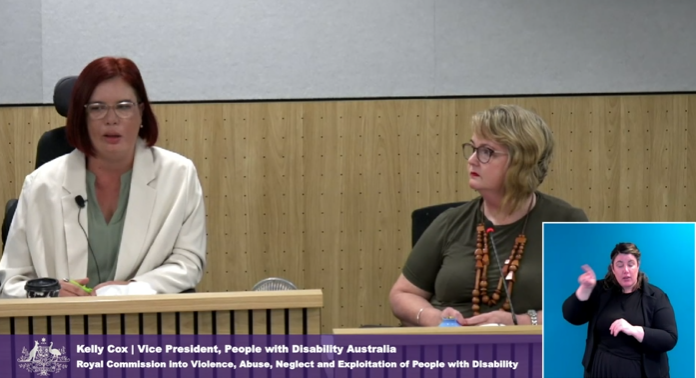

Kelly Cox

“…we need to put that disability or CRPD lens over existing laws and seeing whether they are in line with it, and they need it, and can people’s rights be realised under existing laws.” “We need people to care about our rights as disabled people, and when they don’t care, we need a way to enforce it,” “…we need the Disability Representative Organisations and disabled people involved in whatever gives the outcome and the way forward…. All of us, not just the non-Aboriginal people or the straight people, it has to be the whole community.”

Frances Quan Farrant

“We have used the CRPD in our systemic work and we refer to it constantly in our systemic work, in all the reports and submissions that we make…Then in our individual advocacy, this is where it gets very, very difficult. Because the application of the CRPD in individual advocacy is actually more of an education exercise. Because the CRPD has not been fully implemented in domestic law across jurisdictions. So we have advocates across Australia who are navigating various pieces of legislation and whilst the CRPD, yes, it’s our benchmark, yes, it’s what we want to see, we are working with legislation that doesn’t recognise it, let alone recognise disability rights. So we are faced with barriers all the way, barriers for the people that we are working with, in order to operationalise human rights for people with disability.”

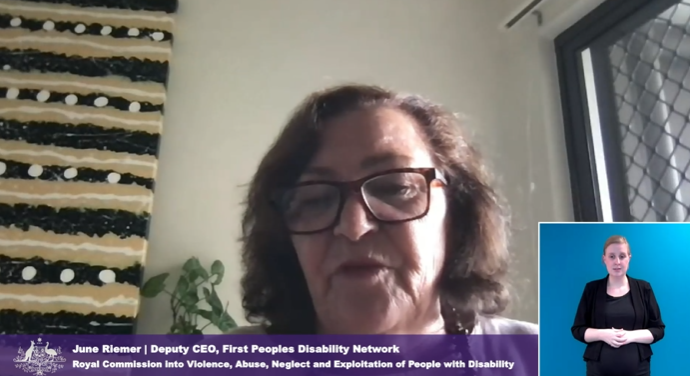

June Riemer

“The funding of the NDAP program needs to be further monitored and supported, there’s currently not enough advocates nationally. That was one of the recommendations with the National Disability Advocacy Program. There is not enough First Nations advocacy groups, and we need more work around supporting self advocacy for people with disability.”

Damian Griffis

“There is still such a sensitivity on the part of some governments of the term “advocacy”, it’s often viewed as perhaps adversarial and I think we need to change the way government systems think about it. It’s not necessarily about adversarial outcomes, it’s about support providing to a person with disability so they can participate in community life.” “…we also need to recognise that our advocates must have capacity to get out into regional and remote Australia. I think that still remains an untold story in many ways. The COVID situation has exposed this only further. The situation for many First Nations people with disability in regional and remote Australia, to be blunt, is one of abject poverty. The only way to get meaningful support to our community members out there is to go see them on country and try and seek support. So the National Disability Advocacy Program is inadequate in funding… There needs to be a specific First Nations disability advocacy program, …and we need it to be implemented a decade ago, where that case has been well and truly made but it needs to have within a recognition that it has to be about engaging all of our communities across regional and remote Australia as well.”

The experience of women and girls with disability with a particular focus on family, domestic and sexual violence (Part 1)

13 October

Women with Disabilities Victoria Senior Policy Officer Jen Hargrave

Jen Hargrave

“…It’s not that we are born inherently vulnerable and isolated and that we can’t fit in. We have public transport systems that aren’t accessible. We have people on income support that leaves them below the poverty line…we’ve got employment rates for people with disabilities way below the OECD average, way below, we are really lagging, and we combine that with what we know about women in employment and how underpaid we are, how much unpaid work we do. All of this leads to us being isolated.

We are also easily discredited and for decades we’ve been hearing stories from women telling us how the perpetrator of the violence, whether it’s a partner, a parent or a disability support worker, is seen as having so much more credibility than they themselves are, they are easily dismissed as being crazy, attention seeking. And all of this allows the perpetrator to hide in plain sight, as we might say so, he is helping her with her money, he is helping her with her medical appointments…. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg”

14 October

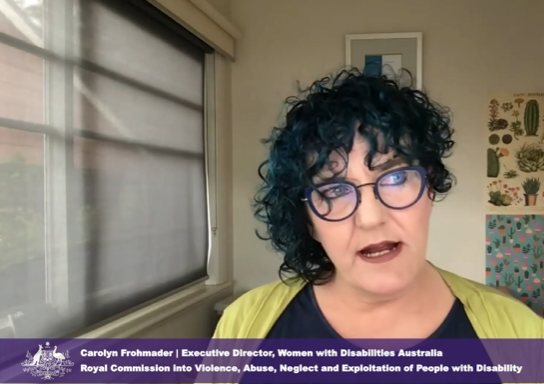

Women with Disabilities Australia CEO Carolyn Frohmader

Carolyn Frohmader

“If we look at women and girls with disability and we look at some of the ways their rights are denied in this way, we can go through things like forced and coerced sterilisation, forced contraception or limited choices around contraception, denial of sexual expression, poorly managed birth and pregnancy, forced and coerced abortion, termination of parental rights, denial of marriage or, alternatively, forced or coerced marriage, exclusion from sexual and reproductive health information, education, services, screening. Everything from things like breast and cervical cancer screening, bone density screening, menopause services, to name just a few.”

First Nations children with disability in out-of-home-care

24 September

Aunty ‘Maggie’ (who has been supported by First Peoples Disability Network)

Aunty ‘Maggie’

“I got to meet Deb and Deb has been a ray of light, a light coming to the end of the tunnel, support, keeping me calm without losing it, and I mean if I didn’t have Deb at my side, I know that she’s here in spirit because her spirit connects with my spirit and the people that she helps… I’m saying it because of the compassion, her being an Indigenous strong woman…

She became an advocate in the end where I was not being listened to and Deb would email them, Deb would be a part of my conversations with DoCS [Department of Community Services] at times and she’d turned around and spoke to them on their level where because I know so much but I don’t have the knowledge what youse have got and what she has.

So to be talking about human rights and listening to me practically cry at times, the comforting words. I mean I don’t know how she does it, but she does it… I mean it’s been strength after strength and that is what’s helped me.”

The experiences of people with disability, in the context of the Australian Government’s approach to the COVID 19 vaccine rollout

17 May 2021

Self advocates and members of VALID Suzannah MacNamara, Greg Tucker, Uli Kaplan and Anthony Reid

Suzannah MacNamara, Greg Tucker, Uli Kaplan and Anthony Reid

Uli: “…there’s a lot of, there’s lot of information coming thick and fast very quickly, overwhelming. Some of it is misinformation…”

Anthony: “basically there’s a lot of people with a disability that’s a fair way, through all the group homes, that might be on different medications which I’m thinking the vaccine might somehow try and interact with the medications they’re on. …. That could be a handy one of information to have coming out for people with a disability.”

Suzannah: “I’m not sure that I want to take it because I’m really scared of taking it as well…. Because I’m a bit nervous that I might, could die at a young age and I don’t know if I would actually take it or not, so I’m really scared of having it…. I’m still deciding, yeah.”

Greg: “Well, I don’t really need that much information. When –when I can get the vaccine, I will do it, for sure … I mean, we are a much smaller country than, say, the United States and they already have, like, 200 million people vaccinated already and we only have 2 million people vaccinated here. So, yeah, I mean. I just want to know, like, because the last thing I heard was Australians probably won’t be fully vaccinated until the middle of next year.”

Inclusion Australia CEO Catherine McAlpine

Catherine McAlpine

“…the advocacy organisations that are our members have been sort of overrun with people calling or contacting them trying to find out when they might get the vaccination, or concerned that they haven’t heard anything. …we had been having regular meetings with the Health Department and we understood that people in group homes were equally a priority as people in residence aged care and we were not aware that such little progress had been made and we were not aware that in fact there had been an internal decision to prioritise people in residential aged care over people with disability…”

Tara Elliffe (who has leadership and advisory roles at Down Syndrome NSW and Council for Intellectual Disability, and has co-hosted Inclusion Australia webinars about COVID-19)

Tara Elliffe

“I had to wear a mask the whole time, then I had to get a badge on my wrist, then I went in to get a sticker as well, and then it was – then I got my vaccine and it was – I was fine….

…it didn’t hurt a bit. … It’s okay to have it. Just do it.”

The experiences of people with cognitive disability in the criminal justice system

24 February 2021

Intellectual Disability Rights Service (IDRS) Executive Officer Janene Cootes and Advocate Michael Baker

Janene Cootes

“…one of the features of the way that we felt was important to do this work was to build a person’s capacity, and a big way of doing that was to involve them in the decision‑making. Too often in court processes, decisions are made for people, but the more somebody can learn the way things happen and make their own decisions and have their decision respected, I think that makes a very big difference to how the person goes forward and to their skills to cope better and do better.” “…the criminal justice system often talks about disability but doesn’t really acknowledge the impact of that disability on the person and why they need additional help, that you might say somebody else didn’t do what they were told to do, okay, but a person with cognitive impairment, there could be a hundred little reasons why things fell through that are not necessarily their fault. I think it’s just a very important understanding.”

Michael Baker

We were able to work with them intensively and individualistically to find the right support coordinator. Perhaps it was a matter of the participant’s NDIS plan not having enough support coordination funding, so we would work with them to address that, sort of begin that review or appeal process to garner more funding that matched their needs more adequately. We did a lot of community engagement work to find appropriate organisations that could reliably provide support coordination services to criminalised people with cognitive disability in relation to the whole suite of service systems which oftentimes they rely upon. So the difficulty really sat with the notion that oftentimes this client group is involved in multiple service systems, so as I mentioned earlier, mental health, drug and alcohol, the criminal justice system, NDIS, housing and homelessness, family and domestic violence; so for a support coordinator to be able to effectively work with that person to manage that range of needs, there certainly needs to be enough NDIS funding there for that, and also that support coordinator certainly needs to have a level of skill and experience to negotiate and coordinate that range of supporting services and the problems that will ultimately arise, because I do just want to add that those many different service systems, while they all touch and get involved with people with cognitive disability, don’t necessarily speak to each other; when they do, they don’t necessarily speak the same language. So that certainly requires a centralised person that is experienced enough and funded enough to manage that with and for the person.

Self Advocate and member of IDRS Making Rights Real advisory group Taylor Budin

Taylor Budin

‘Making Rights Real’ is “all about really, there’s like five of us and we all have different disabilities and impairments and we all sit in a group and we discuss ways on how to train police and other organisations on how to actually deal with someone with a disability who needs to be spoken to by the police or needs to go to court or anything like that. ” “…More educated and stuff like that, because the way I was treated is not right. Like just because I can’t have certain food types does not mean you don’t have the right to say, “I don’t give a f…. if your food touch your peas touch your corn.” Like, it’s things like that. All we ask for is to be spoken to a little bit more nice. You don’t have to treat us like crap — it’s not the right thing. We’re in here doing what we have to do, we’re in here doing our time, you don’t need to make it any worse than it already is” “…How many people are in [prison system] that needs to be on the program, not in. …They don’t know it exists. I really would like to get something back into the system. Yes. There’s a lot of people in there that don’t have the support or advocacy. Just getting pushed under the rug…”

Geoffrey Thomas

“…no one will pay attention. He gives me a voice. They give me a voice. That’s very important to me. Which to me, I don’t know, it might be like I’m overstating it, but when you spend as many years as I have trying to fight corruption within the system and even sometimes trying to fight that corruption within the very system that investigates that system, through omission even, they do not even have to do something, unfortunately just by omission, you’re guilty for not advocating for that person.

It’s refreshing to see that something new is on the horizon, that we can grow and grow and grow into what should be the future. Because more jails is not the answer…”

25 February 2021

CID Advocate and IDRS Justice Advocacy Service Participant Justen Thomas

Justen Thomas

“…I do a lot of advocacy and motivational speaking, talking to young generation Aboriginal kids and that. … I do it with passion, you know.” “…It’s good to be able to talk and the officers would listen. Having that voice and being motivated to be able to do it.” “….I give advice on law enforcement is that you never underestimate a child, you never know where they come from and you don’t know what kind of trauma they are bringing. Please talk to them like they are talking to your friend, and try and be mindful, try and be a role model for good, instead of using tactics on kids.”

Education and training of health professionals in relation to people with cognitive disability

16 December 2020

Council for Intellectual Disability (CID) Inclusion Project Worker Laura Naing (also the NSW Representative on Inclusion Australia’s Our Voice Committee)

Laura Naing

“I am Laura. I have intellectual disability. I’m very proud to be doing this PHN project. Educating and making awareness for a better health system. I want to help people from the towns, communities and rural regions to access health services …I’m an Inclusion Project Worker at CID. I will be educating and making awareness for people from CALD backgrounds to access these services and to promote training and resources – people with disabilities, like me, not to be afraid to speak to doctors….We will do the training for doctors and health people. We will deliver resources for doctors and health people how to access the National Disability Insurance Scheme”

Pathways and barriers to open employment for people with disability

7 December 2020

Speak Out Association of Tasmania Self Advocate Kalena Bos

Kalena Bos

[Speak Out Association of Tasmania] are an advocacy service for people with disability, an agency member of Inclusion Australia …I was 19 and I participated in this program called Adorable, run by Speak Out …It’s a woman’s program about women looking after their health, confidence and wellbeing …[As an Advocate at Speak Out] I work on a committee for Inclusion Australia and I was on members executive …I talk with people around Australia, we make decisions that are important for people with intellectual disability.

Catherine McAlpine

“…Inclusion Australia has been at the lead of a lot of work around open employment for many years, and we have made many submissions to Government. You spoke in your opening address about the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool case, and Paul was an expert witness then. So we have continued on that work, having a real focus, because we believe that for people to live truly inclusive lives, that employment is critical to that because employment is where you meet people, where you are valued, where you create your own income for your own quality of life. It is critical to the wellbeing of all people, including people with disability and people with intellectual disability.”

8 December 2020

National Ethnic Disability Alliance (NEDA) Policy Officer Dominic Hồng Ɖức Golding

Dominic Hồng Ɖức Golding

“…my role would be to look at what avenues are available. What they wanted, and to actually try and make contact with the potential employer and explain them the background, what they can do, what mechanisms they could use to support the potential employee, and also I would ask or request that at least there can be a three day probationary period so that they can demonstrate to the employer that they can actually do the job. And on many occasions they can actually can do the job; they just needed a bit of extra allowances and support around communication needs…”

The experiences of First Nations people with disability and their families in contact with child protection systems

25 November 2020

Intellectual Disability Rights Service (IDRS) Advocate for Parents Julia Wren and Solicitor Kenn Clift

Julia Wren

“They need to have a fair go, so I think it is very important to have somebody as a non legal advocate for these parents because they can stand by and they can support the parents to speak for themselves, advocate for themselves. If they don’t want to, then I will speak for them. And it keeps the DCJ [Department of Communities and Justice] workers accountable, and they have to listen to what the parent has to say.”

…the first contact I will have with the parents is probably — it will be an advice appointment. I will speak to them and then it may be a matter where it seems that one of the larger issues is that the disability is being focused on rather than the parenting. If that is the case, then I might and if I have the capacity I may take the matter on as a court representation matter… If I’m able to be involved early, we might be able to support the parents, have meetings with the Department and they may not file a care application. However, if they do file the care application… I would look at taking the matter onto represent them in court.

‘Kate’ is a parent with disability, a former client of IDRS and a member of the Making Rights Real advisory group

Kate

“They need to acknowledge the parents who have disabilities, like they need to let them have a chance of actually being able to parent their children, and not just rip them away. And also be able to let them show that they can actually be good parents and like put more supports in place, really. Like the intensive family support services, for example, like they were great. And I would recommend it to, you know, other parents who have disabilities to, like, if they have got a FACS involvement or whatever to get that service in place, because it is really, really good, and like for them to keep their children it is important.”

Barriers to accessing a safe, quality and inclusive school education and life course impacts

12 October 2020

Panel of advocacy organisations:

- Queensland Advocacy Incorporated (QAI) Director Michelle O’Flynn and Education Advocate Nikki Parker

- Family Advocacy Executive Director Cecile Elder

- Children and Young People with Disability Australia (CYDA) CEO Mary Sayers

Nikki Parker

“There is this culture of compliance, it seems, where teachers are compliant to principals and the regional office backs the principals. There’s also a dramatic power imbalance. Individual parents trying to fight the very big Department of Education… So it’s a highly emotional, stressful period. A number of people today have used the word “battle” and that’s often a word that we hear from our clients…”

Michelle O’Flynn

“What we have noticed, however, is the moment an advocate is engaged, there is a significant change in response from the school and from the Department with better outcomes for students. So advocacy makes a big difference.”

Cecile Elder

“Parents tell us [the complaints process] is quite hit and miss and more than likely by the time a parent gets to the time of needing to actually call an advocacy organisation, they’ve already tried to resolve the issues happening locally for their sons and daughters… it’s absolutely not uncommon for families to turn up for a meeting …and to be there with five, ten staff from that particular school system that are actually then, in many respects, creating a real power imbalance between the parent actually advocating around the rights and the interests of their child and the school and their position on things.”

“Across States and Territories there’s very few mechanisms which are independent where families can get issues resolved… allegations of abuse such as restrictive practices, we note that in many cases these are not independently investigated and school systems investigating school systems… this is compounded by a lack of funding for independent disability advocacy in each of the States and Territories, and in many States there’s no funding for education advocacy which can work with families to help resolve these issues.”

Psychotropic medication, behaviour support and behaviours of concern

22 September 2020

Watch the Pre-recorded evidence of Raylene Griffiths (Council for Intellectual Disability (CID) project worker)

Raylene Griffiths

“Education and training is the key. Get the management to help people to better live together. Give people choice about where they want to live and who they want to live with. Match, match people to live together who are more suited to living together. Like, different backgrounds, interests. Problems, not seeing eye to eye, making them feel welcome in their own house so that we can experience peace and quiet in the house we’re living.”

23 September 2020

Independent Advocacy North Queensland Advocate Joanna Mullins

Jo Mullins

“…advocacy is a bit of a singular job. We’re not counsellors, we’re not advisers, we’re not lawyers. Our job, in essence, is to be the voice of people with a disability who for whatever reason cannot speak up for themselves. So we help them explore what they want to achieve, what their options are for achieving it and we speak up for them and help them achieve their goals.”

Watch the Pre-recorded evidence of Dianne Toohey (Manager) and Kathy Kendell (Disability Advocate) from Speaking Up For You (SUFY)

Dianne Toohey (left)

“…we first get to know the person well. We spend time investigating the issue that they might come to us with about, and then we talk to people that may know them, know the person well as and what’s going on with that person. Then we develop an advocacy plan with a vision and strategies of how we’re going to work with that person. We involve the person as much as possible in all the meetings and all the actions we take, we talk about with the person first.”

Kathy Kendell

“I think we come from an entirely different perspective that many people do, particularly service providers, and those who might be in senior positions trying to administer a hospital or different areas of government. We come from a perspective that respects a human rights framework and often while there is lip service paid to those principles and legislation, often we find that we’re up against a standing culture that sometimes reacts very differently…”

24 August 2020

VALID Advocate Dariane McLean

Dariane McLean

“…I will gather people around the table, really, to talk, and to try and figure out, you know, why the system around this person is falling down…More often than not the key question that nobody sort of raises is, has anybody asked the person what they want? What is, you know, what’s bothering them? And inevitably people will sort of be surprised at in a question because the person’s presentation is so complex that there’s an assumption that they don’t have a view on what they want.”

Queensland Advocacy Incorporated Advocate Courtney Wolf

Courtney Wolf

“..what we have seen here at QAI, especially, is that the chemical restraint can limit a person’s freedom unnecessarily.…the way that we see behaviour is that it’s expressing a need, and when people are given chemical restraint it’s just subduing the symptoms of a behaviour rather than actually addressing an unmet need or someone’s desire for something. …medication can be looked at as the easiest way to subdue someone’s behaviour without actually going through and working with them and their family and their support team around how to best support them around their behaviours of concern.”

Experiences of people with disability during the ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic

18 August 2020

Senior Counsel Assisting Dr Kerri Mellifont QC

[Advocacy groups] “speak about the challenges faced by them during the pandemic. Advocacy groups have been instrumental in providing accessible and timely information. Many advocacy groups have been inundated with calls for help, ranging from people needing to get access to essential, personal requirements; people who simply could not get access to incontinence pads; they couldn’t get food; people who are trying to navigate and understand the publicly available information; people wanting to know what they can do to try and make sure that their child, a student with a disability, is provided accessible education and is simply not left to fall so far behind there is no hope of catching up.”

Disability Justice Australia Inc (DJA) Senior Disability Advocate Fiona Downing and People with Disability Australia (PWDA) Director – Media & Communications Eleanor Gibbs

Fiona Downing

“…because the advocacy sector is so drastically underfunded, we just don’t have the capacity to reach out to all the former clients and people we think might be in trouble. Unfortunately there has been no emergency funding for advocacy in Melbourne, despite the issues that have arisen and in fact this financial year we’ve had a cut to NDIS appeals funding. And this is right in the middle of the pandemic. So advocacy services are just constantly having to turn people away. People often can’t even get their names on a waitlist because we have to close our waitlist as a way of managing all the advocacy requests that are coming in.”

El Gibbs

“So for a disability advocacy organisation, how we’ve funded it, we all have a lot of time in rebalances sitting there, and other work has had to be put aside because the immediate crisis for people with disability has been so great. So our individual advocates in particular have worked tirelessly while they have had their own challenges of working from home and working remotely…” – “We certainly know of people with disability who have been without phone and internet and have not been able to report that and only because of an existing relationship with advocates have we found out what has been happening and been able to intervene and I know other advocacy organisations have had that.”

19 August 2020

Council for Intellectual Disability (CID) Senior Manager – Inclusion Projects Rachel Spencer

Rachel Spencer

“…so a lot of people with intellectual disability rely on public transport, whether that be to get to work or out in the community and to visit family and friends. It is one of the biggest issues that our membership and our advocacy group raise. So it’s not surprising that it is still an issue during this COVID period.

People are nervous about, I guess, being in public places and in confined spaces. They are concerned that other members of the public won’t necessarily respect the rules or the guidelines around physical distancing and so there are the risks for people who are actually going to still use public transport, but then there is the risk for people who won’t use it and, therefore, become more isolated.”

Women with Disabilities Victoria (WDV) CEO Leah van Poppel and Every Australian Counts Campaign Director Kirsten Deane

Leah van Poppel

“…whenever we talk to women with disabilities, one of the key issues that comes up is isolation. And that’s isolation from services, it’s isolation from supports like family and friends. It is just a general lack of connection sometimes to the outside world.…more women are telling us that they have fewer support workers or fewer family and friends coming to their homes when they are really worried about the complications of COVID and the effect that it could have on them. They might die. So that imposes more isolation on women who may already not have many connections at all.”

“The more advocacy services and safe spaces for women so they are supported in a range of different ways throughout the pandemic to reach out to women, the better, because there may be instances where women are not able to disclose violence by picking up the phone and calling the Family Violence Service. But if they have access to social gatherings, if they have access to advocacy around disability, they are given other safe spaces.”

Kirsten Deane

“…in addition to the NDIS issues, we need more funding for advocacy, both systemic and individual advocacy. During the pandemic I had cause to speak to a number of advocacy organisations either to refer people for help or to share information and resources. And I am aware that many advocacy organisations have closed books and some of them have even closed their waiting list. I think in the middle of a global pandemic when people urgently need help, that isn’t acceptable. We also need funding for systemic advocacy because it is those organisations that are working with government to make sure that government responds appropriately and that people aren’t left behind.”

CID Member and Self Advocate Anthony Mulholland

Anthony Mulholland

“We would go to the shops. We would do banking. We would do our post shop. But everything’s now changed during the coronavirus. And there were regulations …Obviously it’s hard to adapt to change, and I found it really hard because I’m not confident in using online, I’m not confident using technology. I’d rather see somebody face‑to‑face. And that’s what a lot of my friends would like to do. And it also gets them out of the house, because a lot of them are lonely and we live by ourselves, like me, and we just want to meet people. And so interaction in the community was something that I’m concerned about, particularly during coronavirus…”

Watch the Pre-recorded evidence of Speak Out Tasmania Self Advocate Kalena Bos

“…the Premier, when he was talking on the TV, it was very confusing and hard to understand… Speak advocates did a Speak Out Live every night at 5:30 … On Facebook… they told us what we could and couldn’t do… they also showed us how to get on a bus, but, to be safe.”

Health care for people with cognitive disability – Sydney hearing

18 February 2020

Kylie Scott (member of the the Down Syndrome Australia Advisory Network)

“…a fair few of… people in my case ….of people with intellectual disability – a fair few people. They’re hiding in ghettos but they don’t seem to get out. So for them to – people with disabilities, to find their voice and to be heard and, of course, live in the independent living as much as they can.” “…Mr Commissioner, I want to speak up for people who can’t speak up. We all need to be understood and supported. “

Council for Intellectual Disability (CID) CEO Justine O’Neill and CID project worker Jack Kelly

Justine O’Neill

“When people with intellectual disability are able to lead and make decisions, then we’re all able to use our rights and participate. And we need to hear directly from people with intellectual disability about how to do that and what good support needs to be. I think in the context of this hearing around health, we’re going to hear a lot of stories about what happens when people are not involved in their care, when the people who support them are not heard, and the really negative consequences that comes from that sense of people with intellectual disability just being to the side and not participating in their own lives.”

Jack Kelly

“I always think it’s really important to just trust your inner self, because you’re you for you. Like, it doesn’t matter what other people say or do and … actions; it’s just important that you make the right decisions for you no matter what, whether it might be health that we’re talking about today or in another area in your life… I’ve seen a lot of people disheartened because they’re not getting the choice and control that they want, or they get frustrated because another person is making that decision for them.”

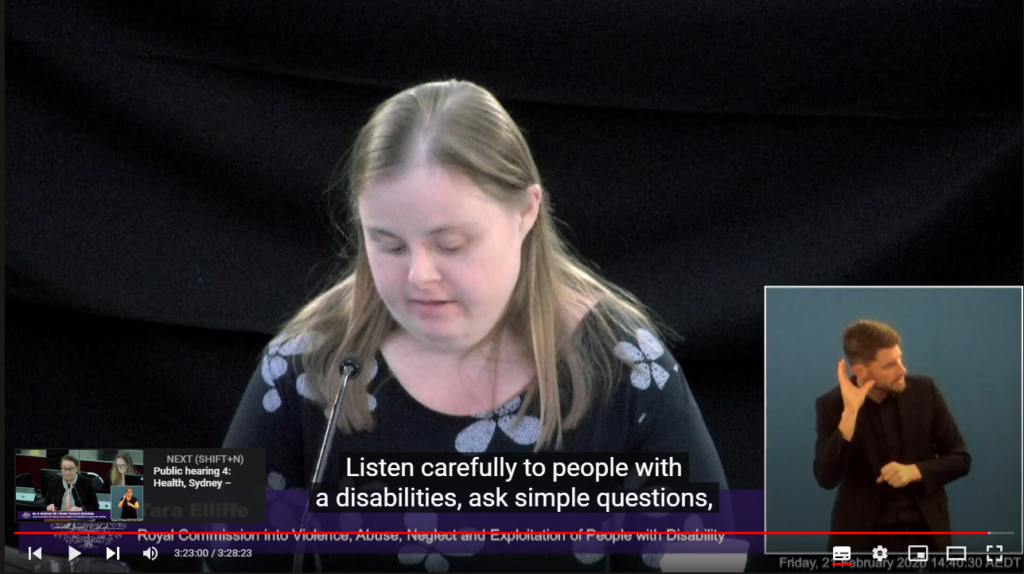

21 February 2020

Tara Elliffe (who has leadership and advisory roles at Down Syndrome NSW and Council for Intellectual Disability)

Tara Elliffe

“I have a lot of things that I think doctors and hospitals can do better. Listen carefully to people with a disabilities; ask simple questions; use pictures to help people understand; answering people’s questions; talk to me and not my parents; have documents in Easy Read. Also, think doctors and nurses should have disability training…”

25 February 2020

Council on Intellectual Disability (CID) Senior Advocate Jim Simpson

Jim Simpson

“…our approach to our work is to very much be informed by those things that you mentioned, that the experiences that people with intellectual disability tell us about, the experiences that their family members tell us about are absolutely key to our being and our advocacy. But the – complementing that with working with professionals in the field and being able to rely on the research base which has gradually developed in relation to health care, for example, provides an invaluable combination to then inform the strengths and strategies for our advocacy.”

28 February 2020

Self Advocacy Sydney co-founder and board member Robert Strike AM

Robert Strike AM

“…also, their parent or their advocate with them, to make certain they are being listened to, because that’s important. If you don’t have people listen to you and understanding what you’re saying – that’s the most important for any person with a disability. Because I believe that we can try and do it together as one, and work in a better system.” …”Being treated as a person, first and foremost. Making certain I understand what they’re saying is important too. And it’s important for people like me – can understand totally and carefully”

Homes and living – Melbourne hearing

2 December 2019

Jane Rosengrave, Self Advocate (with AMIDA, Reinforce and STAR Victoria) and First Peoples Disability Network board member

Jane Rosengrave

“… since I have lived in the city in the flat I am free as a bird, I am, and that’s the way it’s going to be for the rest of my life.”

“yes, I can speak up for myself. I’m a fighter, I am, …and I teach other people that they have got a voice to be heard…”

4 December 2019

Victorian Advocacy League for Individuals with Disability Inc. (VALID) CEO Kevin Stone presented with Alan Robertson

Kevin Stone

“…our advocacy has developed and our networks have developed right through group homes particularly across metro but across the State and we empower people to set up their own resident meetings and – and talk directly to management about the issues that they encounter.”

Alan Robertson

“…that was our hell. Staff were allowed to do what they like. Bash you up, clip you over the ears, do this, do that.” — “Meals same, meals, well, haven’t got the choice of meals. When I was put in an institution, there was no choices. In those days you were given what you were given. Was – I think it was fish and chips Friday lunchtime. Nothing like what you’ve got now. As I said before, you’ve got freedom now, and that’s how it should be. I’ve been lucky in my life…. everyone behind me, the last few years, see inside of me and the outside of me, you see the difference where – how do I explain – I’ve become a bit more mature, because I’m out and I’m living in the community.”

5 December 2019

Panel of advocacy organisations:

- Women with DIsabilities Victoria (WDV) Acting CEO Nadia Mattiazzo

- VALID Advocacy Manager Sarah Forbes

- Action for More Independence and Dignity in Accommodation (AMIDA) Project Officer Pauline Williams

- Reinforce Self Advocate Colin Hiscoe

- Villamanta Disability Rights Legal Service Solicitor Naomi Anderson

Nadia Mattiazzo

“Women with disabilities who are experiencing violence whether it be in group homes or in other situations, we need to listen to them, we need to listen to what is happening and we need to believe them. We need to develop gender sensitive approaches. Understanding the – the differences and the needs of women with disabilities.”

Sarah Forbes

“I think we are constantly both shocked and dismayed as advocates at how little people understand about their rights. They do have rights that they don’t know about, and that they don’t exercise. They also have experiences of attempting to exercise their rights and not being respected. Or in fact being retaliated against for doing that. Being laughed at for suggesting that they should be able to make certain choices. Having certain choices used as collateral, as punishments. So I think there’s – people receive very mixed messages. They receive the message in Victoria that “It’s OK to complain”, but what happens when you do is often not what was promised.”

Pauline Williams

“…the group home model doesn’t really lend itself to discussions of rights because, in reality, people’s rights aren’t respected and – I mean, we have terrible cases of abuse and violence that we advocate for people to get resolutions to, and time and time again, we find that there’s just blockages. That it takes, sometimes, years to try and get resolution when people are actually in situations of violence and abuse. So it’s minimised when people complain. No resolution comes; no action is taken. So why would anyone think that they had rights. And – and we find that, as advocates, that it’s just so frustrating when, you know, we’re constantly trying to push for solutions and there aren’t any.”

Colin Hiscoe

“…yes, we are here, we are coming, we are talking about what our knowledge and experience is of people with a disability in group homes. Fantastic, great. Congratulations. Well done. Pats on the back all around.

But I don’t think that you are getting to the real people that matter. This Royal Commission is about people in group homes. I think you need to get there into the group homes. The biggest problem might be that no matter what you do, the people there are going to be really scared, they’re going to be afraid, they’re frightened of retribution, they’re frightened of being in trouble, they’re frightened of being hit, whatever, and they’re really scared.”

Naomi Anderson

“For people with disability to be free of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation, they need to know that the community has their back. They need to know that when people do things that are unlawful or illegal that they will be protected and that action will be taken to ensure it doesn’t happen again. And until that happens, we’re letting everybody down.”

Education and Learning – Townsville hearing

4 November 2019

Independent Advocacy North Queensland CEO Deborah Wilson features in a panel on inclusive education

Deborah Wilson

“… we see all the time – because the child’s disability is not taken into account, there – there is no inclusion. That does develop extra behavioural issues. These behavioural issues lead to suspension time and time and time again. There is always the excuse, you could say, that there is not enough resources, there is not enough funding.”